Amber Butchart’s The Fabric of Democracy: review

Fashion and politics may not seem a likely partnership, but as I learned when I visited the T-Shirt – Cult – Culture – Subversion at the Fashion and Textile Museum back in 2018, logo tees have long been a way of getting a message across creatively and unexpectedly. The museum’s new exhibition The Fabric of Democracy, curated by Fashion Historian Amber Butchart proves to be the perfect follow-up to that, this time focusing on how textiles have been used as a way of circulating propaganda by governments, regimes and corporations, and there isn’t a leaflet or protest banner in sight.

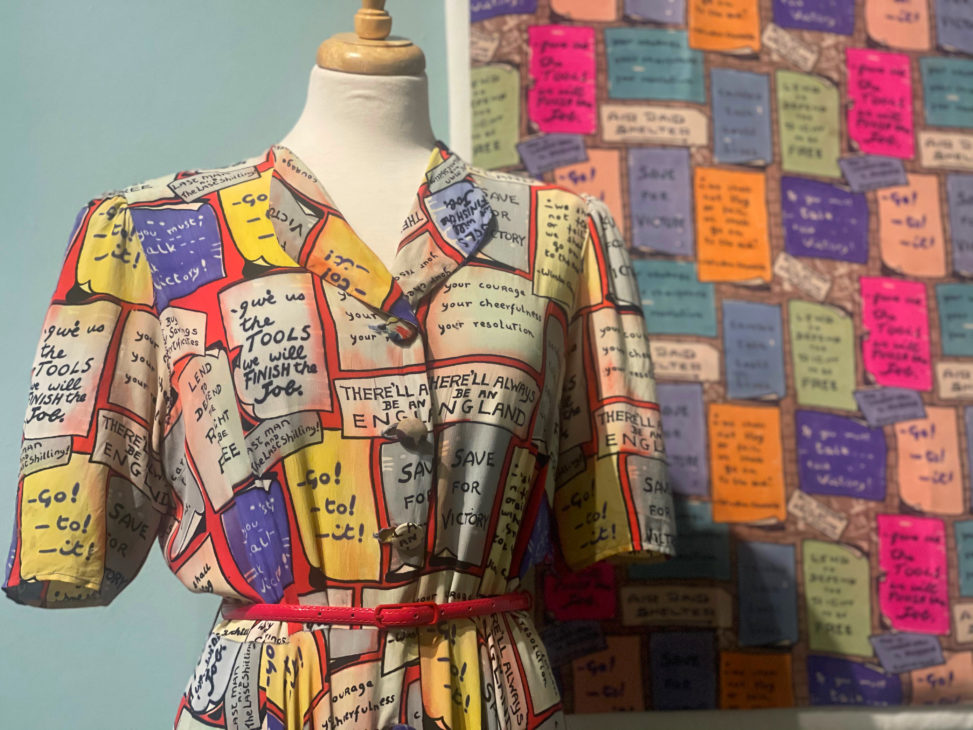

The Fabric of Democracy takes a more aesthetically pleasing approach, infiltrating messages into pretty dresses, cosy duvet covers and even handkerchiefs. Some of it you wouldn’t notice at first glance but inspect closely and you’ll see the messages unfold.

Amber has brought together over 150 individual items from across the world that tell secret stories within the threads. Featuring printed clothing and homewares, The Fabric of Democracy charts this clever use of creativity with examples from her own collection, the museum’s archives and some very special donations. Intrigued? I was.

This is a topic that is completely new to me, so it was a treat to get an exhibition tour with Amber who explained the significance of the samples on show.

Visiting The Fabric of Democracy at Fashion and Textile Museum, London

There’s a lot to digest so take your time visiting this exhibition. Laid out over two floors, there are numerous glass cabinets and panels to read. It feels more ‘museum like’ than other exhibitions I’ve seen here. The lower floor delves into war, conflict and revolution while upstairs takes a more positive spin on things with textiles that have been used to commemorate national occasions.

Making history accessible and relatable is what makes Amber’s work as a historian so valuable. Everyone that visits her exhibition will have a different takeaway, but here are mine….

5 things I learnt from visiting The Fashion of Democracy exhibition

1. Wearing flags is only one form of nationalist fashion

There’s been no shortage of opportunities to dress up in Union Jack aesthetics thanks to recent royal activity in the UK including a jubilee, a death and a coronation. It’s fascinating how people who would never usually go near a British flag embrace it for a day. To be fair, I’m one of them. I had no qualms about dressing in red, white and blue and waving a Union Jack when I attended numerous jubilee events including a cockney knees up. There’s a sense of unity and positive spirit, being part of something. But outside of those festivities, the flag is a no-go area for me.

From one perspective it’s womenswear with a nautical design, on the other hand, it glorifies colonisation and slavery

I don’t want to associate myself with nationalist sentiment and yet I have done so, unintentionally and that’s the thing with propaganda and textiles, you’re giving out subtle messaging without realising. But it’s also not just about flags.

The exhibition features several examples where it looks like you could be wearing a perfectly innocent scarf, yet look closely at the design and there’s a hidden message that promotes nationalist ideas.

One of these is the map prints. As Amber explained: “we think of maps as entirely factual depicting geography but really they depict imperial ambition and imagined national boundaries – they’re political statements not necessarily geographical facts.” Examples include a robe on display from Imperial Japan showing invasions in China.

There’s also a chintz skirt thought to be from 1755-99 featuring images of Dutch West India Company ships, from one perspective it’s womenswear with a nautical design, on the other hand, it glorifies colonisation and slavery.

2. Textiles can have hidden meanings

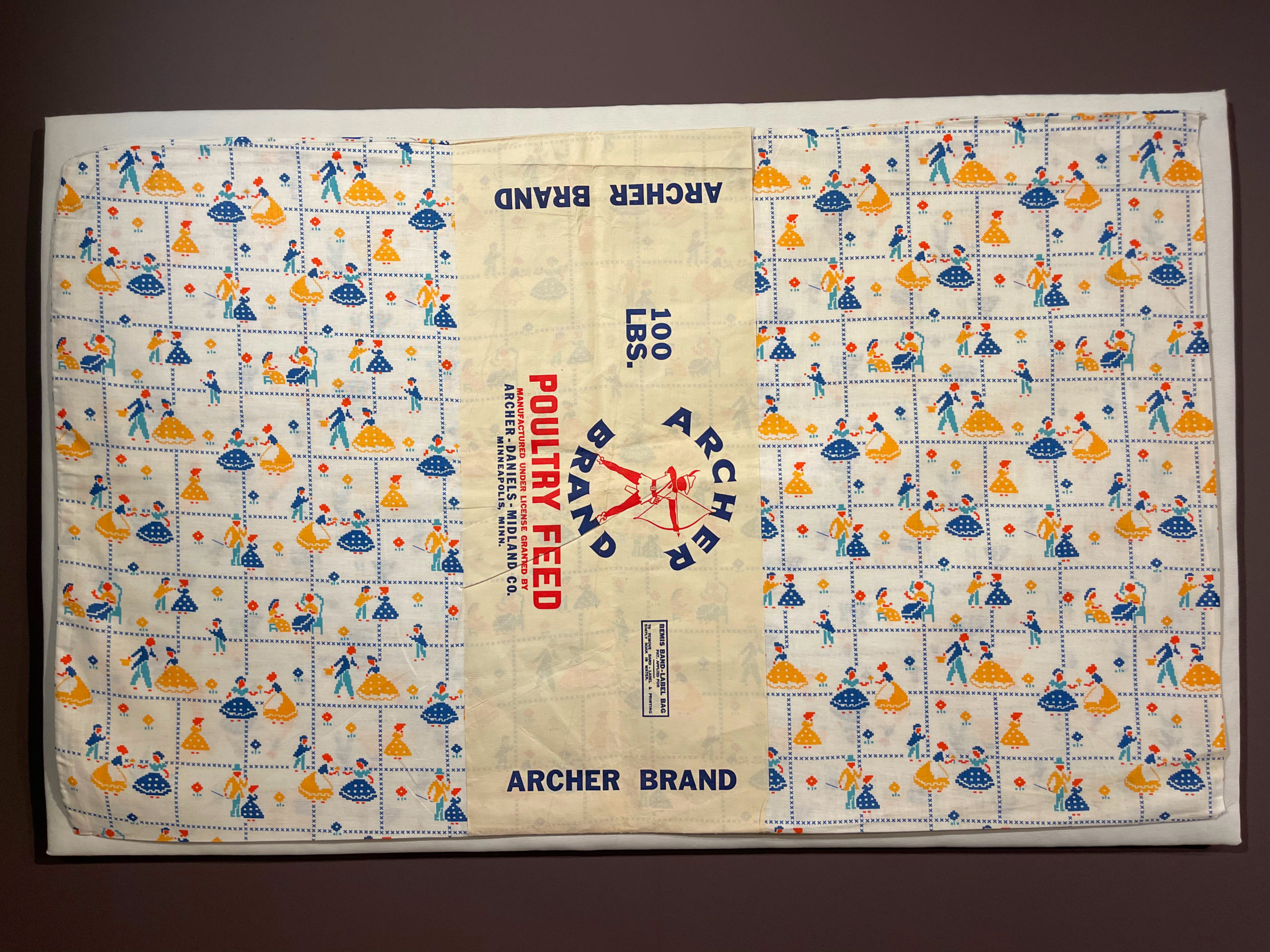

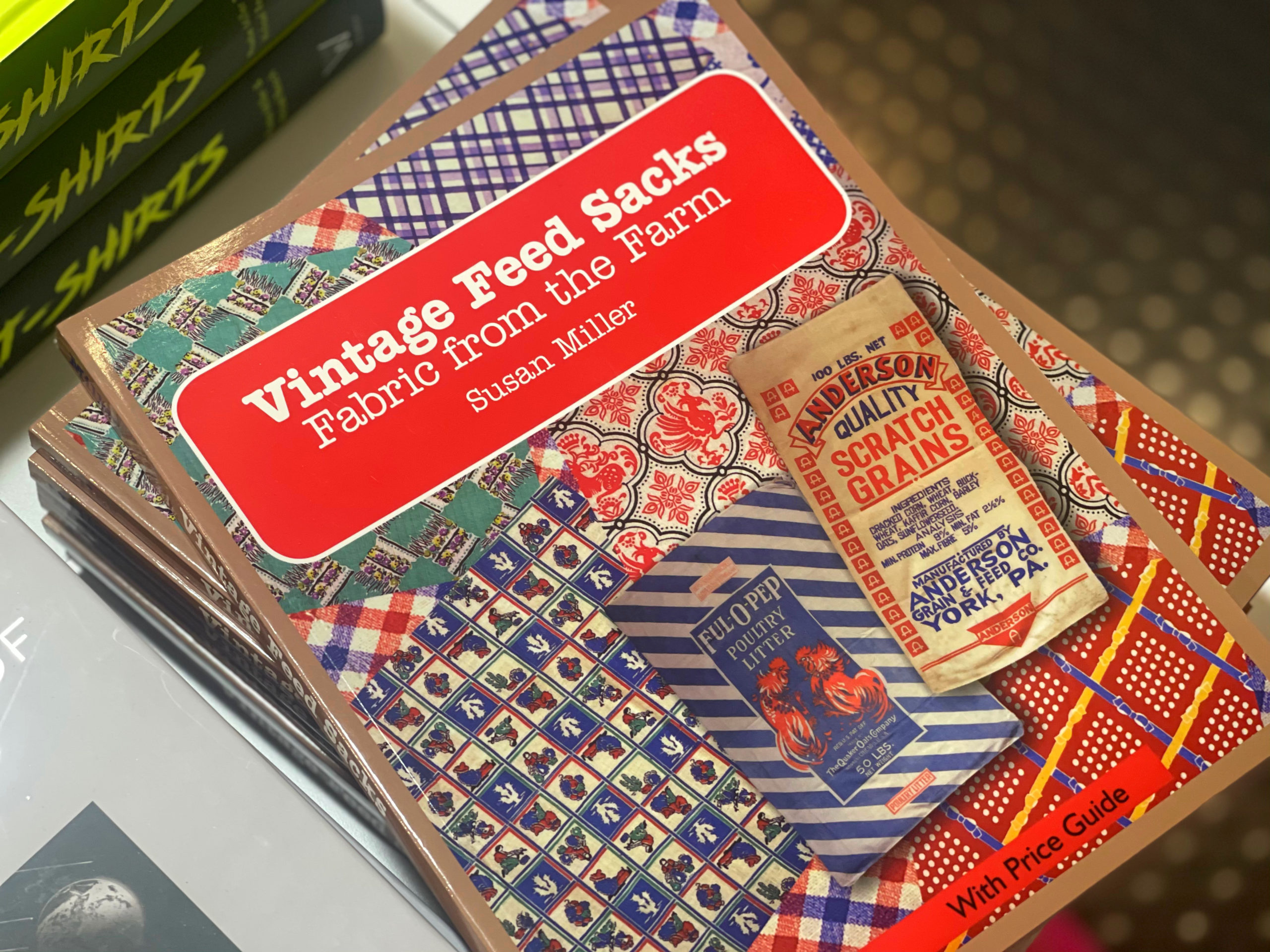

My favourite section in the exhibition was the American feed bags, a concept that was new to me but I could get behind thanks to its sustainability credentials though that wasn’t the motivation at the time.

These were literally bags that your chicken feed would come in if you were a farmer, but they weren’t just plain sacks, as Amber explained: “feed bags were decorated with prints so they could be repurposed afterwards either turned into clothing or things for the home. The idea was the man was the farmer but his wife would be like ‘oh I’m after this one, make sure you get that one because it’s got the print that I want.’ The idea of this ingenuity really feeds into ideas around American national identity and self-sufficiency, especially in rural populations.”

If you’d like to see more feed sack fabric there’s a brilliant book in the museum shop with examples.

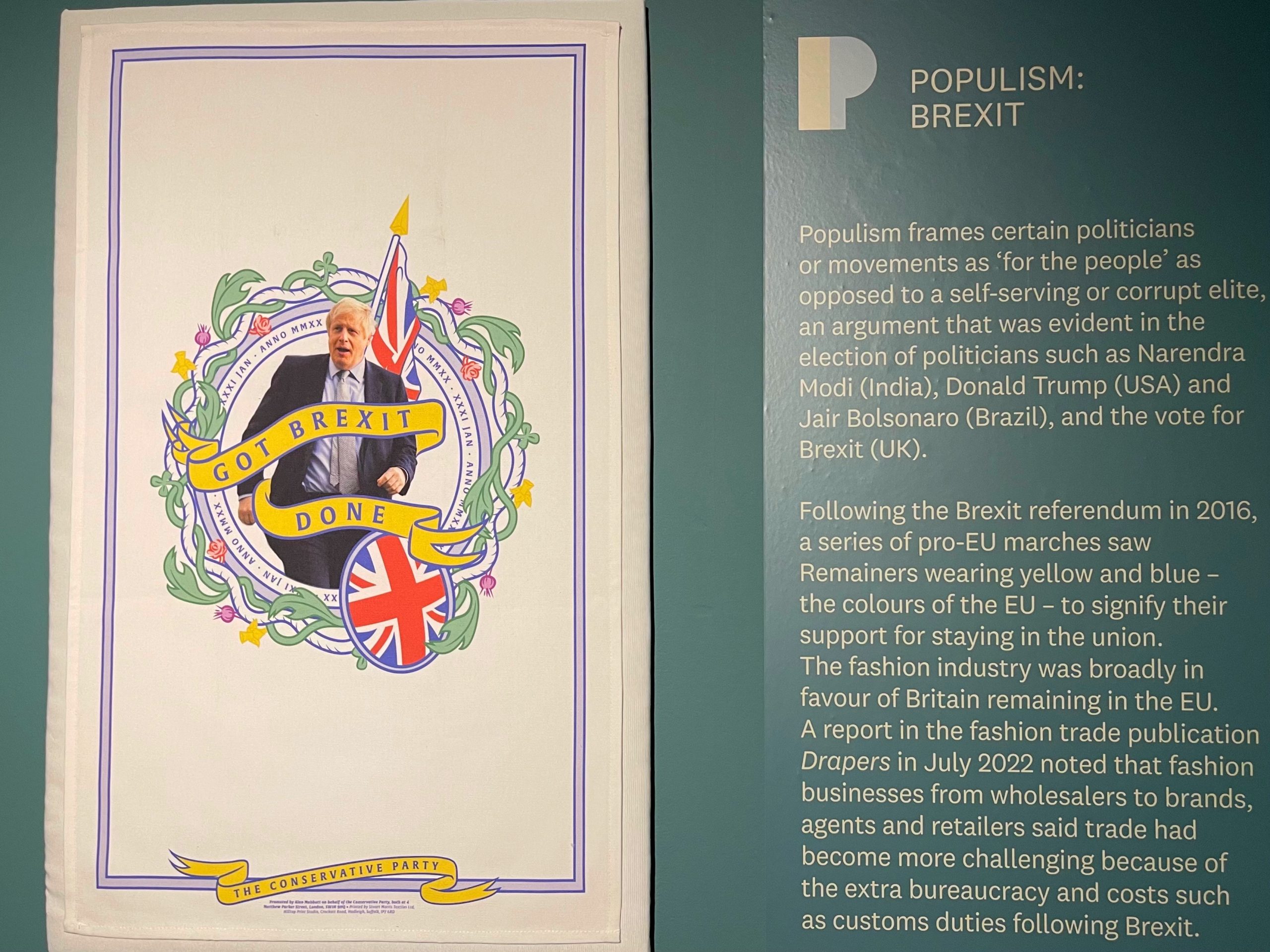

3. There’s some scary merchandise out there

Some things you can’t unsee and the Conservative Party Brexit tea towel is one of them. It was sold on the political party’s website for £12 back in January 2020 then removed when the global pandemic hit. Emblazoned with the words ‘Got Brexit Done’ many people assumed it was a parody yet it was official merchandise. Amber admitted she didn’t enjoy having to purchase one: “I bought it on Ebay and paid a lot more than £12, it was the most gutting money I’ve ever had to spend.”

She went on to explain that not everything is what it seems – the towel may look like ‘Brexit’ has been a success, but it’s a “false show of unity. The flowers depict daffodils to represent Wales and thistles for Scotland but they didn’t all vote to remain in the EU.”

4. Propaganda can be very subtle

It’s a piece of psychological warfare to ruin morale encouraging soldiers to stop fighting so the war would end

On the ground floor, there’s a scarf in a cabinet display that’s not as innocent as it seems. Amber explains: “The handkerchief was dropped by the Chinese People’s volunteers in South Korea to be picked up by American service man. It’s a piece of psychological warfare to ruin morale encouraging soldiers to stop fighting so the war would end. It says ‘those who love you want you back home safe and sound’ and ‘Merry Christmas’ trying to persuade soldiers to put down arms and go home for Christmas.”

Though the scarf shows a date of 1951, this form of propaganda continued. Amber said they’ve been seen as recent as 2014 and as tensions ramp up again in the present day they could return.

5. Not all propaganda is bad

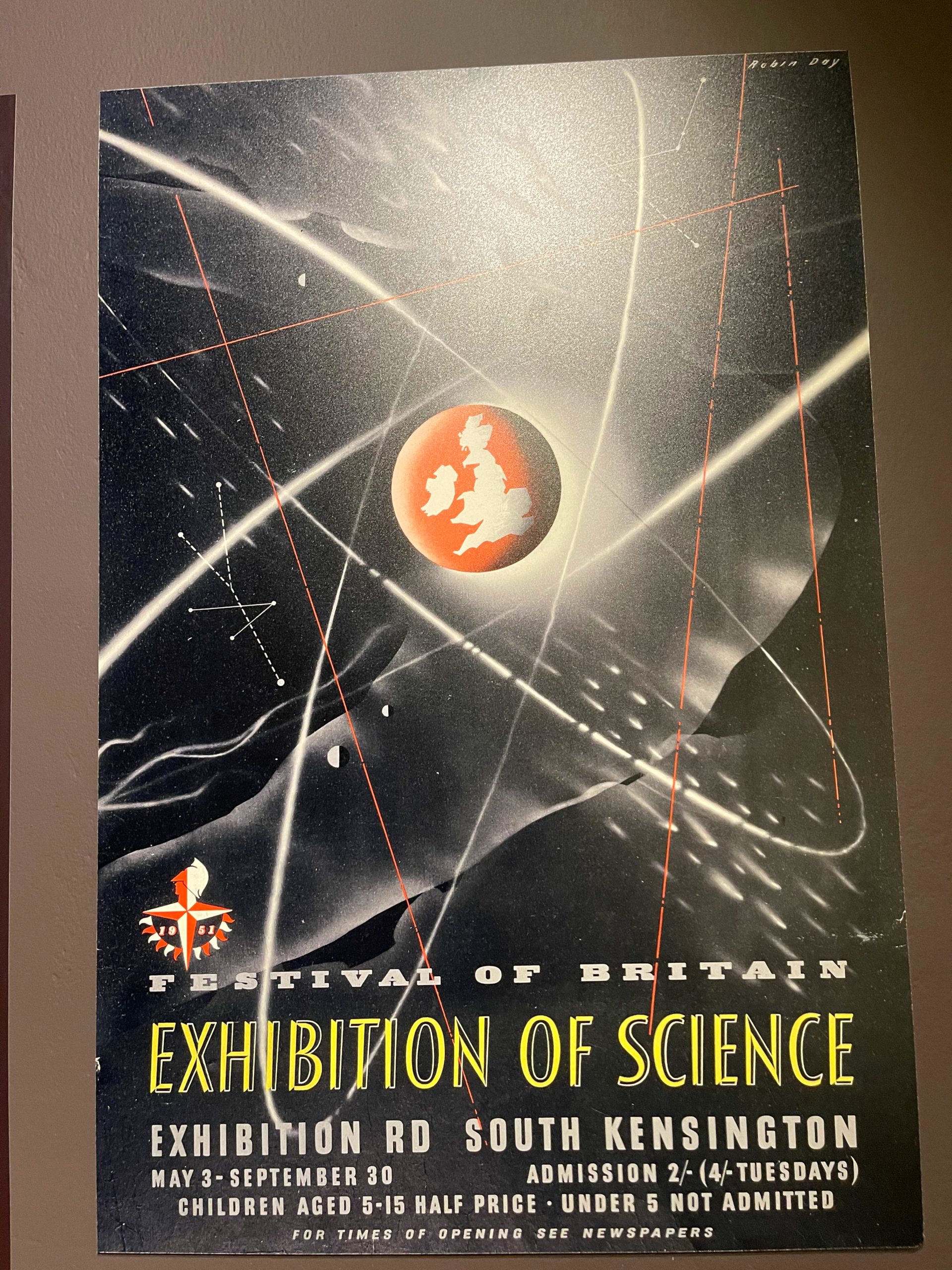

Boosting morale and uplifting the mood of a nation tends to have a positive effect like making people feel good about themselves. Messages about celebrating success are a form of nationalism that is appreciated even though there’s another agenda behind it. Examples of this in The Fabric of Democracy exhibition are scarves that celebrate the Olympic Games and a section on 1951 The Festival of Britain.

A red dress has the Festival of Britain logo woven in to look like a fashionable motif but really it’s a way of showing the notion of Britain being ‘Great.’ Amber explained: “Celebrations and coronations solidify national identity. The 1951 Festival of Britain was a tonic during a time of austerity. As a nation we saw great things happening like the formation of the NHS. There were also developments in science and promoting modernity.”

This is illustrated by a dress made from jet plane print fabric designed by Lucienne Day, who was an influential post-war designer. Celebrating the jet engine it was inspired by a poster for a Jet exhibition held in 1946. The exhibition was by the Ministry of Supply who were the government department responsible for aeronautical research and developing atomic energy.

I appreciated having this balance of seeing propaganda through a different lens and it’s a key takeaway for me. One thing I did ask Amber about was why other than a kanga depicting Obama, African fabrics which have long carried messages in wax prints, have been left. She explained that they deserved an exhibition in themselves and a different type of curation which I fully respected and support.

The Fabric of Democracy inspires a new way of thinking about and observing textiles. I plan to keep an eye from now on to see if I can spot these acts of clever propaganda in fashion and other areas of everyday life.

Visit The Fabric of Democracy: Propaganda and textiles from the French Revolution to Brexit at Fashion & Textiles Museum, 83 Bermondsey Street, London, SE1 3XF. Open 29th September 2023 to 3rd March 2024. Tickets cost: £12.65 www.fashiontextilemuseum.org

https://www.fashiontextilemuseum.org/exhibitions/the-fabric-of-democracy