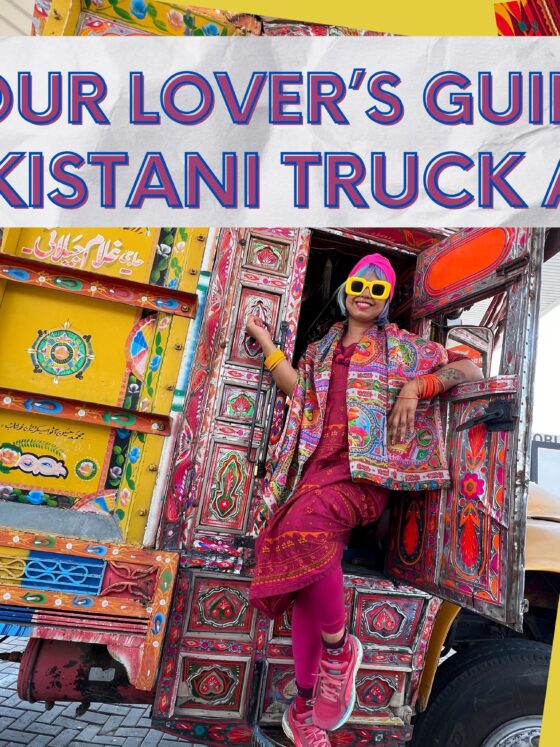

Learning about silk weaving in North East Thailand

Skeins of naturally dyed silk

Silk is considered by many as the finest fabric in the world: but how many people know how it’s really made? I’ve heard of silk worms and I’ve heard that silk comes from silk worms, but how exactly? I’ve also heard of people that boycott silk because they don’t think it’s ethical, and met others who revere the textile, produced by silk weaving.

One of the unexpected highlights of my recent visit to North East Thailand was a visit to the Queen Sirikit Sericulture Centre, Sakon Nakhon, to see for myself, how silk is made.

Cocoons under development

Cocoons under development

What is silk weaving?

Sericulture is the term given to the farming of silk worms for the purpose of making silk. Silk weaving has been part of Thai culture for centuries, especially in the Northeastern region. Practiced mainly by women, sericulture comprises cultivating mulberries, rearing silkworms, producing raw silk, dyeing silk thread and weaving it into silk – all aspects I was able to see at the centre.

Silk cocoons being boiled before the silk can be extracted

We were shown around by the owner of the farm who proclaimed very early on that in order to get silk, there has to be death: silkworms have to die, otherwise you simply don’t get the silk from them. I found this an extremely difficult concept to grasp and initially while others in the group observed the various steps, took photos and tried the weaving techniques out, I simply didn’t want to be part of it. I just couldn’t grasp the concept of silk worms being blanched in hot water (killed) just to get the silk taken from them. But as the experience progressed I became more open to the idea and ended up eating a dead silk worm…but more on that later.

Our visit started with looking at the centre’s mulberry bush orchard.

In order to breed silk worms you need a constant supply of mulberry trees. The process begins with a silk moth who lays eggs which then hatch into silkworms who eat the mulberry leaves.

At the centre I saw tiny newborn worms that looked like moving dots and then observed the older more developed, fully fledged worms – I even picked one up and held it.

Up close and personal with a silk work

Up close and personal with a silk work

The worms eventually ‘weave a cocoon’ around themselves, which is made of silk threads. This can take about two to three days. The cocoons feel solid and when I first saw a tray of them, they reminded me of a cheese flavour snack we get in the UK called Wotsits.

Empty cocoons that look like Wotsits!

Left as they are, the cocoons will hatch and become silk moths, starting the process off again. But in order to make silk, the cocoons are boiled, which kills the worms (currently in pupae state) – these are extracted and eaten, a delicacy and good source of protein, while the silk filaments that make up the cocoon are extracted – this is the raw silk which then needs to be spun into thread, in the same way wool is.

One of the reasons silk is considered so precious is because very little silk is created by a single cocoon – an estimated 2,500 cocoons would be needed to make a small batch (a pound) of silk, which would barely stretch to a garment.

In the grounds of the centre we met two women who were doing the part of the process whereby the cocoons are boiled off, the pupae extracted and the filaments collected. This was the stage I found difficult to watch, I just couldn’t get my head around the worms having to die in order for humans to get silk. But as I got a better understanding, it dawned on me that it’s not as bad as it sounds. The other thing that truly fascinated me was just how natural the origins of silk are – the very fact that silk worms have the capacity to create silk is a miracle.

The reason I decided that silk production was not as bad as I first thought and eventually gave it a go, was by understanding more about ‘pupae’. During this stage the ‘insect’ is going through an ‘inactive’ stage – it’s neither larva or an adult, it’s merely in a state of inactivity, so it could be argued that it’s neither dead or alive. It’s not like a happy worm is going about its day and then boiled alive and feels the pain: it’s completely unaware and technically not a living, breathing being.

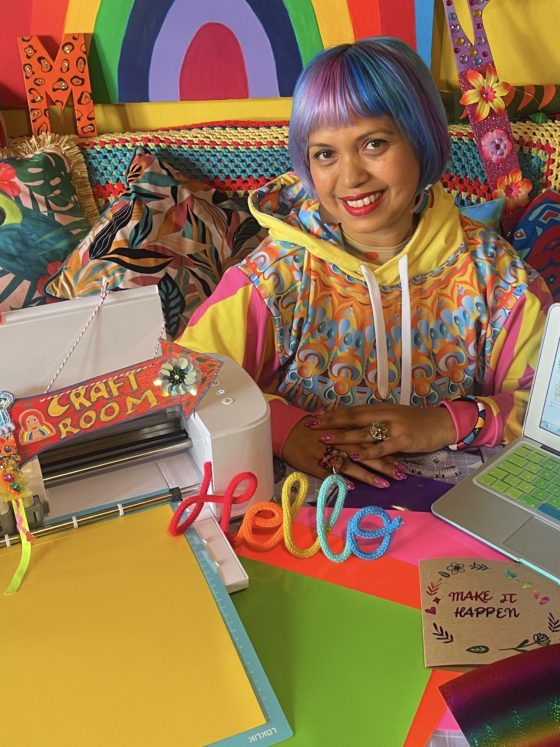

Craft and Travel’s Momtaz finally giving silk weaving a go

Craft and Travel’s Momtaz finally giving silk weaving a go

Once I was comfortable with that I was able to give the silk extraction a go. It was a delicate operation and repetitive and I admired the women for doing this for so many hours.

In order for the process to continue there needs to be a steady supply of moths too and for this reason some of the cocoons are simply left aside and allowed to develop. While I was there I managed to watch two moths hatch – it was a slow process but they eventually crawled out and detached themselves.

One of the positive aspects of the process is that no ‘worm’ is wasted. They aren’t killed and thrown away, instead the are eaten – in fact they can be eaten as soon as they are boiled and come away from the cocoon, – they look a bit like mussels. I was skeptical about trying one and I said no for a long time and then at the end I decided this was the only chance in my life to eat one, so I did and it tasted like a very good quality chickpea!

Extracted silk filaments

Extracted silk filaments

Elsewhere in the centre we watched the filaments being spun into thread and these being dyed into various stages using natural dyes.

There’s also a shop at the centre which sells silk fabrics and garments and it’s even possible to buy the threads. Contact the centre to arrange demo sessions if you’re interested in the same experience I had.